In less than a week, a falsehood with no evidence spiraled into trending hashtags, viral videos and even a presidential denial. The episode underscores the power of information cascades in the digital age: once enough people repeat a claim, the perception of truth overtakes the need for proof.

Rumors about the health or death of world leaders are hardly new — Joseph Stalin, Fidel Castro, Kim Jong Un and even U.S. figures like Hillary Clinton and Melania Trump have all been declared dead prematurely. But what has changed is the speed at which these claims can travel and the way scattered pieces of speculation can fuse into a self-sustaining narrative. In today’s polarized environment, it only takes a few days, or a few million clicks, for a conspiracy theory to take on the appearance of consensus.

How the cascade unfolded

The case of President Donald Trump’s rumored death over Labor Day weekend 2025 illustrates how information cascades take shape. Instead of one false claim suddenly catching fire, it was a sequence of loosely connected signals, some benign, others distorted, that converged into a viral story.

On Aug. 28, Vice President JD Vance told USA Today he was confident Trump was in good health and would “serve out the remainder of his term.” He added that if “God forbid, there’s a terrible tragedy,” he had received good on-the-job training. Vance repeated that Trump was “incredibly healthy,” but social media clipped his remark to suggest the administration was preparing for Trump’s death.

Bold claims with no evidence

By Aug. 29, X posts bluntly stating “Trump is dead. He died on Wednesday” had been viewed more than 13 million times. Google searches for “is Trump dead” spiked overnight into Aug. 30. Hashtags like #trumpisdead trended across TikTok, Reddit and Bluesky, generating millions of interactions despite the absence of evidence.

Days before, an unfounded claim that Trump had “six to eight months” left to live was already in circulation, further priming audiences to expect the worst. With Trump absent from public events after an Aug. 26 Cabinet meeting, speculation deepened. Commentators scrutinized photos of his bruised hand and swollen ankles — symptoms of chronic venous insufficiency, a benign condition disclosed by the White House in July — as signs of a serious medical decline.

On Sept. 1, blurry photos of Trump heading to his golf course circulated widely, with users claiming the man pictured was a body double. One post received 3.2 million views. Even Getty Images photos of Trump golfing on Aug. 30 and 31 were questioned, with some insisting they were years old despite clear documentation to the contrary.

Why cascades spread

This layering is what defines an information cascade. Each new post, video or meme, whether citing Vance’s remarks, old photos, Trump’s absence or his medical history, reinforced the idea that something was wrong. Users did not verify claims themselves; they shared them because thousands of others already had.The cascade gained strength not from evidence but from momentum. The very fact that so many people were repeating the rumor made it feel more credible, even to skeptics.

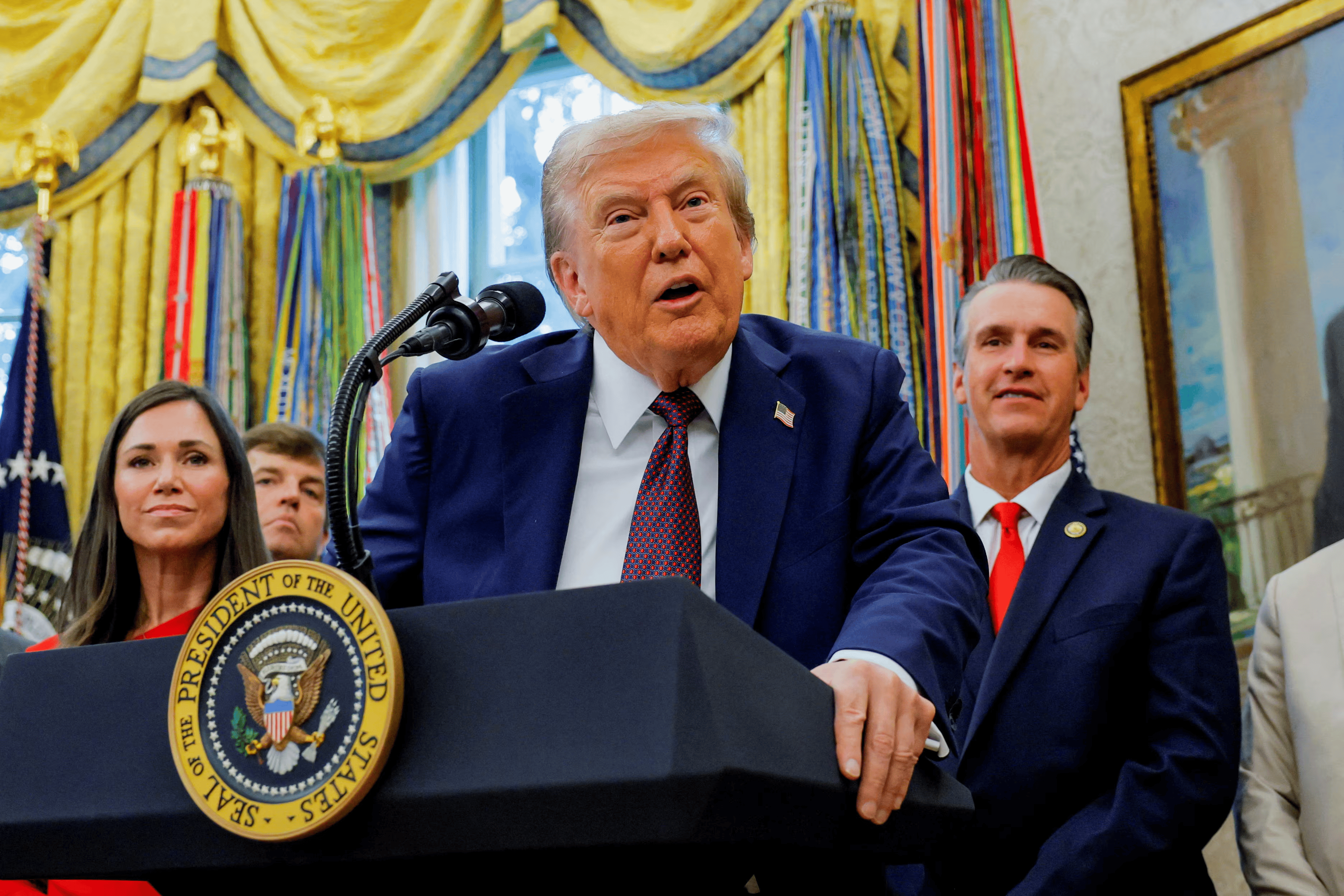

Trump pushes back

As the story built, Trump attempted to puncture it with his own content. On Aug. 31, he posted on Truth Social: “NEVER FELT BETTER IN MY LIFE,” alongside golf photos. At a Sept. 2 Oval Office news conference, he joked, “I didn’t do any [press conferences] for two days, and they said, ‘There must be something wrong with him.’”

When Fox News reporter Peter Doocy asked if he had seen the online claims, Trump replied, “Really? I didn’t see that,” before listing his weekend activities.

The bigger lesson

The rumors eventually subsided. But the story is less about Trump’s health and more about the process that carried a baseless claim to viral heights. In today’s information environment, individual signals like an offhand remark, a delayed appearance or a blurry photo don’t remain isolated. They are woven together online into narratives that take on a life of their own. Once a cascade begins, truth can become secondary. What matters is how many people are watching, clicking and reposting. In this case, a conspiracy with no foundation spread so widely that the president of the United States had to assure the public he was alive.

References

- Charles Trepany, “Trump is alive. So why did rumors of his death go so viral?” USA Today, Sept. 5, 2025.

- Laerke Christensen, “Breaking down rumor Trump died over Labor Day weekend,” Snopes, Sept. 2, 2025.

- Maria Ramirez Uribe & Loreben Tuquero, “How Donald Trump’s untimely and untrue death unfolded on social media,” PBS NewsHour/PolitiFact, Sept. 4, 2025.

- Ben Johansen, Sophia Cai & Irie Sentner, “Trump denies he’s dead,” POLITICO West Wing Playbook, Sept. 2, 2025.

- Associated Press, “Trump says social media conspiracies about his death were wrong,” Sept. 2, 2025.